Definition of Key Terms

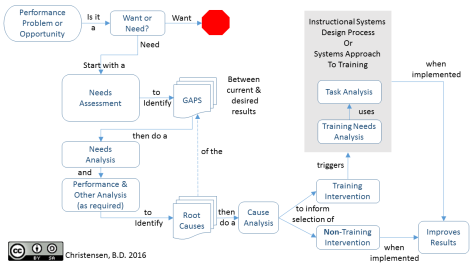

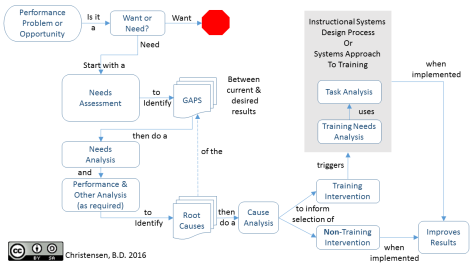

“Need” refers to the gap or discrepancy between a present state (what is) and a desired state (what should be). The need is neither the present nor the future state; it is the gap between them.

“Target Group” Needs Assessments are focused on particular target groups in a system. Common target groups in education settings include students, parents, teachers, administrators, and the community at-large. Ideally, needs assessments are initially conducted to determine the needs of the people for whom the population or system. However, a “comprehensive” needs assessment often takes into account needs identified in other parts of a system. For example, a needs assessment might include the concerns of the “service providers” (e.g. teachers, guidance counselors, or school principals—the people who have a direct relationship with the service receivers) or “system issues” (e.g., availability of programs, services, and personnel; level of program coordination; and access to appropriate facilities).

A “Needs Assessment” is a systematic approach that progresses through a defined series of phases. Needs Assessment focuses on the ends (i.e., outcomes) to be attained, rather than the means (i.e., process). For example, reading achievement is an outcome whereas reading instruction is a means toward that end. It gathers data by means of established procedures and methods designed for specific purposes. The kinds and scope of methods are selected to fit the purposes and context of the needs assessment. Needs assessment sets priorities and determines criteria for solutions so that planners and managers can make sound decisions. Needs assessment sets criteria for determining how best to allocate available money, people, facilities, and other resources. Needs assessment leads to action that will improve programs, services, organizational structure and operations, or a combination of these elements.

Steps

Let’s take a quick look at general steps taken in a needs assessment.

- Exploration and identification. During the first phase of the needs assessment, you need to determine what you already know about your organization’s needs, whether it be additional resources, new technologies, or market expansion. It’s about figuring out where you are and where you want to be. You also need to discover other undisclosed needs that may be hindering you from moving from where you are to where you want to be. You will often rank these needs in order of importance. You will then set the scope of your research. In other words, the needs you are going to focus upon.

- Data gathering and analysis. At this stage you are collecting the information you need to better understand the gaps (needs) between where you are and where you want to be. Data may be collected from internal or externally records through research techniques such as surveys and document-analysis. After the data is collected, it is organized and analyzed.

- Utilization. This is where the data you analyzed is used to create a plan of action and implement it. You will set priorities, evaluate solutions, apply a cost-benefit analysis to determine which solution is best in light of the relative costs and benefits of each, formulate a plan to implement your solution, and then allocate the resources necessary for implementation. Again, the goal is to develop a plan to close the gaps between the desired future state and its current state.

- Evaluation. You will evaluate the results of the action plan against the results: has the action plan placed you closer to where you want to be? Evaluation can help you determine what made an action plan successful or find the errors in your needs assessment. For example, did you miss an important gap, or were the resources you allocated insufficient to close the gap?

What Watkins Say?

Watkins describes analysis as “a process for breaking something down to understand its component parts and their relationships” (R. Watkins, personal communication, June 13, 2016). As to concluded, “A needs assessment identifies gaps between current and desired results and places those [gaps] in priority order on the basis of the costs to ignore the needs. They also stress that the gap is the need.

Figure 1: Needs Assessment vs. Needs Analysis Concept Map V2.0

Source adapt and taken from:

- http://study.com/academy/lesson/what-is-needs-assessment-definition-examples-quiz.html

- https://www2.ed.gov/admins/lead/account/compneedsassessment.pdf

- http://www.ispi.org/ISPI/Resources/PX/Articles/Editors__Pick/Needs_Assessment_vs_Needs_Analysis__What_s_the_Diff_.aspx